IP36: Identifying The Important In A World Where Everything Is Urgent

The Eisenhower Matrix for the "always on" age

I hope that everyone has had a great summer. Since we last spoke, I’ve been busy preparing the manuscript for The Future Habit with Nicklas Lundblad. Much more on that soon.

Identifying the important in a world of constant urgency and noise

This week’s post looks at two former US presidents and how their work habits can upgrade the way public-policy and strategy teams operate in today’s noisy environment.

Abraham Lincoln sometimes drafted rapid, even angry, replies to letters—then put them aside rather than sending them in the heat of the moment. In his archive you can find envelopes marked, “Never sent. Never signed.”

Being able to cool a response before clicking send feels like a luxury in a world of always-on communications.

This links us to Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force during World War II.

It was Eisenhower who provided one of the most useful lines in business thinking:

“I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.” He went on to say, “Now this, I think, represents a dilemma of modern man. Your being here can help place the important before us, and perhaps even give the important the touch of urgency.”

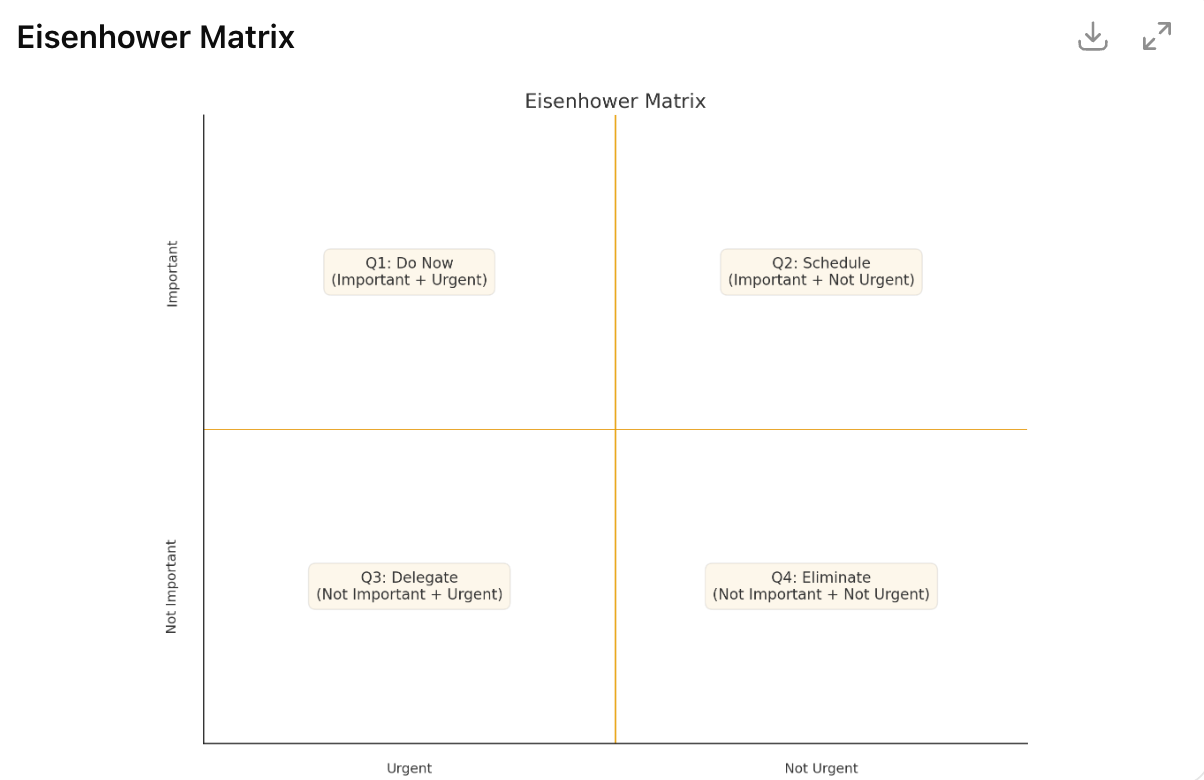

His dictum led to the development of the Eisenhower Matrix:

Quadrant 1 - If it’s urgent and important - do it now;

Quadrant 2 - Important, but not urgent - schedule action:

Quadrant 3 - Urgent, but not important - delegate

Quadrant 4 - Neither import nor urgent - eliminate

If this represented “the dilemma of the modern man” in 1954 when Eisenhower first floated the concept, it is surely even more of a dilemma in an age of constant interruptions, always-on social media and perpetual flurries of noise.

Information overload creates a perpetual now where everything looks urgent. Social feeds demand a response, and corporate messaging tools privilege the ‘now’ over strategy. Urgency has a loudhailer; the work that improves outcomes—analysis, options, testing—rarely shouts. The result is a bias towards urgent-but-not-important tasks and a drift from strategy to tactics.

The always-on nature of modern communications and tech means that it is quite possible to be always responding to the urgent, while ignoring the work that is important to your overall strategy. Consistently responding to the urgent, whilst ignoring the important can have you sprinting off the cliff like Wile E Coyote in the Roadrunner cartoons.

So how do you find signal in the noise and stop the urgent from always trumping the important—especially in corporate public policy?

Getting the diagnosis right

As I’ve noted [in IP33], a good diagnosis is the first part of Richard Rumelt’s “good-strategy kernel” (followed by a guiding policy and coherent actions). Without a shared diagnosis of the regulatory, political and strategic landscape, you can’t judge which pings or “urgent emails” really matter. Building that diagnosis upfront and constantly reflecting on it makes your responses calmer and more accurate.

Identifying your strategic priorities

When priorities aren’t explicit, every urgent ping, message or email can be made to feel like a priority. It’s important to tie priorities to your guiding policy, then triage incoming requests with two questions:

Does this affect a strategic priority? If yes, act. If no, ask:

Does this change the diagnosis or reset our priorities? If yes, update the diagnosis and plan actions.

If the answer to both is no, batch or delegate—don’t let it cannibalise important and urgent work.

Using foresight tools effectively

When considering how to respond in the case of an “urgent request”, it always helps to have considered this response previously. Kneejerk responses are less likely if foresight exercises are intelligently used in advance.

Scenario exercises can be used to consider whether the organisation is prepared for potential events.

War games can be utilised to test organisational resilience and identify potential stakeholder moves.

Premortems can be used to consider failure modes or potential crises before a project ia launched.

Such tools are no longer optional within public policy or broader strategy, instead they’re essential to navigate an increasingly complex, fast-moving environment.

Protect the important, but not urgent

Have all seen when responding to the latest crisis becomes all consuming and public policy teams become focused purely on firefighting. This is important, of course. A crisis can’t be left to spiral out of control, but organisations also can’t be government entirely by panic and knee-jerk to every piece of noise. As such, having institutional focus on the strategically important, but not urgent, becomes crucial. This might be through the carving out of individual teams or holding regular strategy session.

We have all seen teams consumed by the latest flare-up. Crisis response matters, but organisations cannot be governed by panic and public-policy teams cannot focus myopically on firefighting, whilst missing the bigger picture and the importance of proactivity. It’s important to protect the quadrant of the matrix that is important, but not urgent by:

Protecting a team to focus on the important, but not urgent strategic tasks.

Ring-fencing sessions for the broader team to focus on the important and strategic priorities.

Holding regular strategy sessions to review signposts, emerging risks and reconsidering the diagnosis of the strategic and policy environment.

Lincoln’s unsent letters and Eisenhower’s matrix point to the same discipline: buy yourself time to think, always ensure that the important has a guaranteed place within your organisation—before the next “urgent” ping or email arrives.