Almost exactly a year ago, in IP23, I argued that there was room for “techno-optimism” on the left, centre and the right of politics. I suggested that “a more positive (or realistic) approach to tech should stretch well beyond libertarianism and offers potential for the centre-right and centre-left to build a more compelling vision and to develop a more compelling politics.”

A lot has happened since then - Marc Andreessen, the author of the “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” is now a close supporter of re-elected President Trump. Several of his techno-optimist comrades on the libertarian right, most notably Elon Musk and David Sacks, are now directly in the Presidential orbit.

As I predicted in IP32, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book Abundance is now seeking to show that harnessing the potential of technology shouldn’t be a political impulse restricted to libertarianism. Instead, they argue that progressives should use the power of tech to meet progressive goals.

Klein says that this makes him a tech-realist, rather than a techno-optimist (a term he dislikes), as he argues that, without technology, many of the goals most prized by progressives might be out of reach. He uses the example that smart cement, which requires technological advance, is essential for decarbonisation. This is, for Klein and Thompson, one of many examples where technology can be used to pull forward key goals.

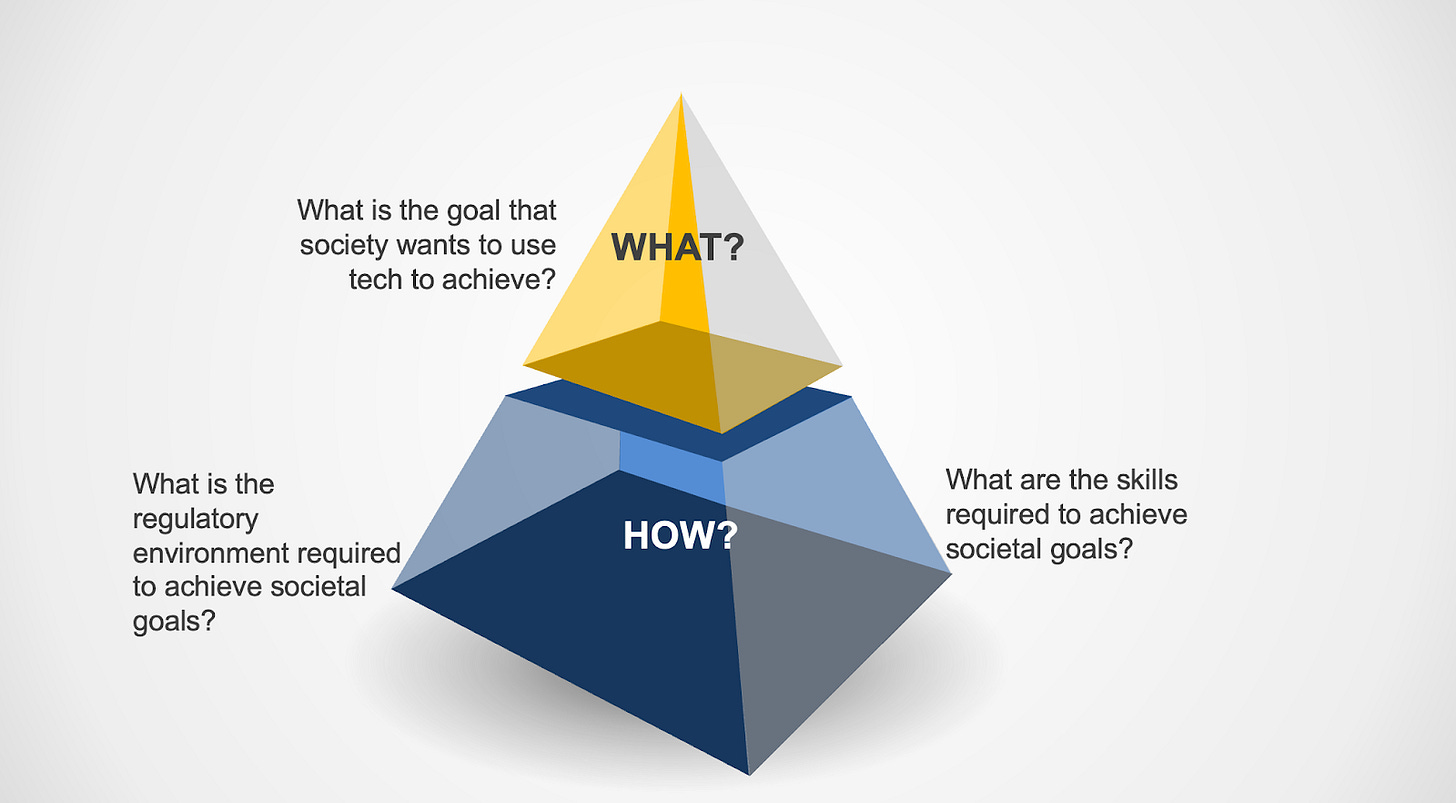

This Substack will consider what the shifting approach to tech, exemplified by Abundance on the centre-left and the Techno-Optimist Manifesto on the libertarian right, means for tech and potentially for politics. I’ll argue that tech has a role to play in helping consider the WHAT (societal goals to be targeted) and the HOW (the skills and regulatory environment needed to deliver these goals).

Considering Abundance

The Abundance argument is pretty straightforward - namely that we should build and invent more of the things we need, in order to create an environment of abundance, rather than scarcity. An early rehearsal of the concept was Klein’s 2021 concept of “supply-side progressivism”, which argued that:

“those of us who believe in a radically fairer, gentler, more sustainable world have a stake in bringing forward the technologies that will make that world possible… It requires inventions and advances that render old problems obsolete and new possibilities manifold.”

The argument behind Abundance is that liberals (and I would argue politicians as a whole) have spent too long obsessing with process and blocking things rather than building things and aiming to achieve ambitious political goals. This is characterised by a housing shortage on both sides of the Atlantic and the failure to deliver ambitious high speed rail projects, such as HS2 in the UK and the bullet train proposals in California.

Similarly, politicians have been driven by a regulatory impulse, developing regulations and programmes, rather than a desire to achieve goals, incentivise invention and build infrastructure and institutions.

Again this, of course, has echoes in the Techno-Optimists of the libertarian right. And perhaps the loudest echo is in Andreesen’s monumental 2020 essay It’s Time To Build, where he called out the institutional failure in the West that was highlighted by the Covid pandemic, but, for him, illustrated in housing, physical infrastructure, transportation, education, manufacturing. According to Andreessen, the problem was inertia - “we need to want these things more than we want to prevent these things.” And he saw the need for both left and right to engage in the project of building:

It’s time for full-throated, unapologetic, uncompromised political support from the right for aggressive investment in new products, in new industries, in new factories, in new science, in big leaps forward… The left starts out with a stronger bias toward the public sector in many of these areas. To which I say, prove the superior model!... Stop trying to protect the old, the entrenched, the irrelevant; commit the public sector fully to the future. Milton Friedman once said the great public sector mistake is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results. Instead of taking that as an insult, take it as a challenge—build new things and show the results!

Klein and Thompson talked about the similarities and differences in a discussion on the Honestly podcast. While some of the most thoughtful people on left and right agree on the need to build, the need to be ambitious and the need to avoid overregulation, they differ when it comes to defining what ends and goals should be, what an ideal society looks like (around tax and spending, for example) and what kinds of regulation might be seen as onerous.

Abundance and Tech

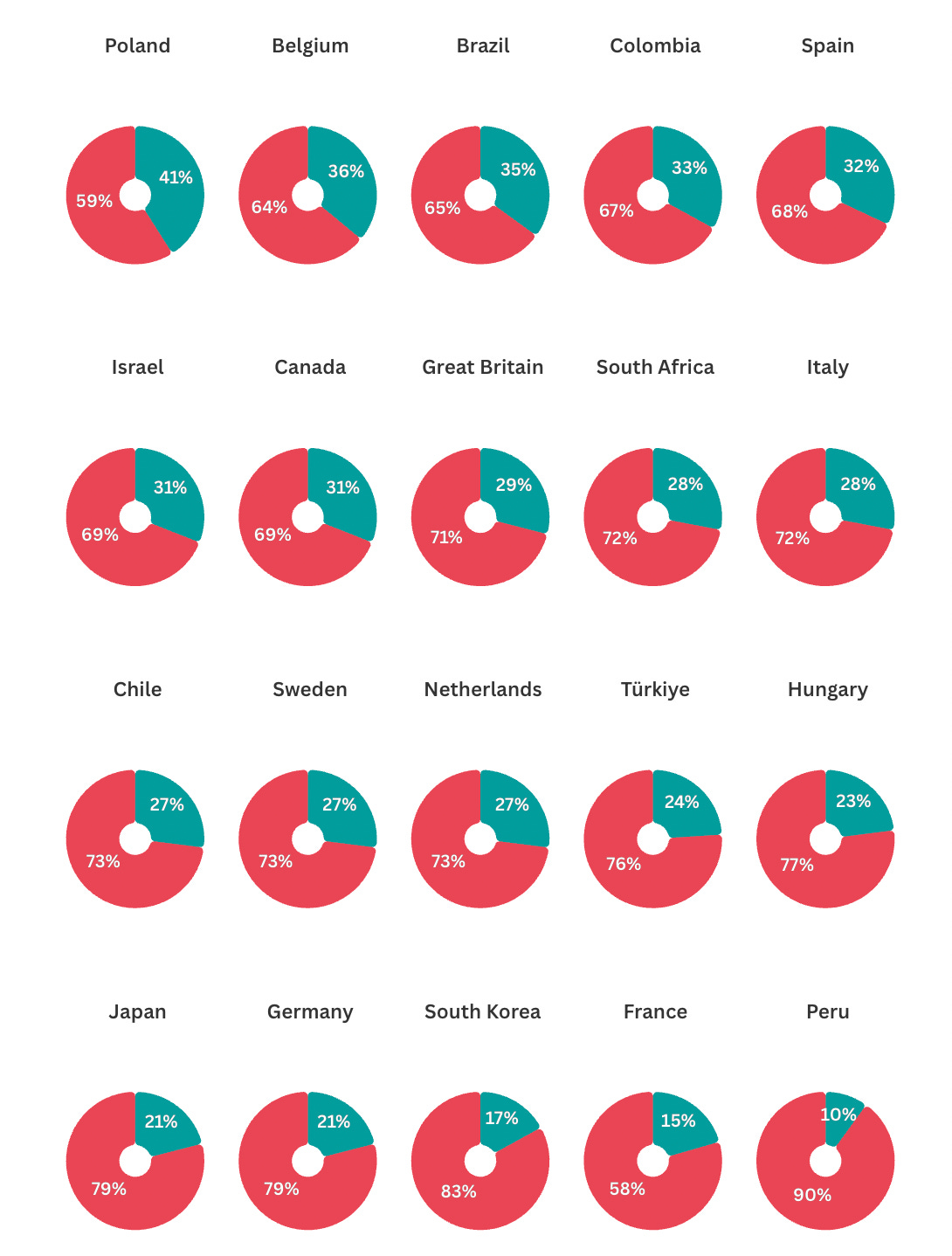

The Abundance and optimist agenda provides a challenge for tech as well. The benefits of innovation and technology are clear - rising life expectancy, extraordinary advances in medicine and reductions in global poverty. But many people in developed countries aren’t necessarily feeling these benefits financially or seeing them in their immediate physical environment, as per the “nothing works” critique. This leads to a belief that technological progress is not leading to societal or economic progress - something starkly illustrated by Ipsos’s recent global right direction/ wrong track polling (with red signifying wrong track):

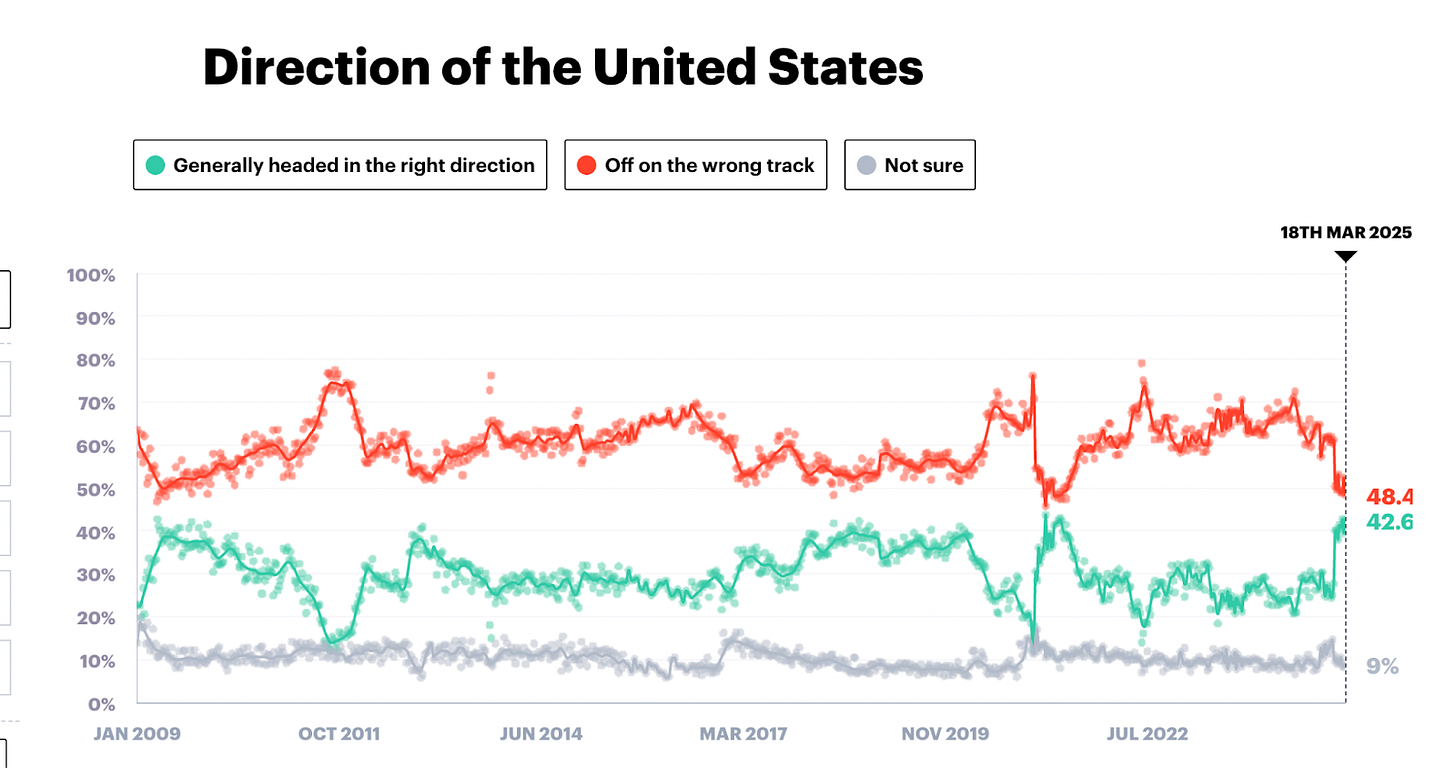

Interestingly, answers to a similar question from YouGov in the United States seem to have become partisan, at least for a short time. Either this is a new trend or it’s a blip.

Understanding how tech might enable societal goals

Klein and Thompson made the strong argument that we need to consider societal goals in order to invent things that meet these goals. This is a clarion call for societal and political imagination.

For tech, it is, of course, important to illustrate how technological advance is directly contributing to those key national and societal goals. Examples already abound, such as the use of Alphafold to understand protein formations and tackle disease and the use of AI to help prevent agricultural diseases.

Historically it has taken a grave national crisis (notably war and pandemics) to achieve coordination between the private sector, academia and government. The successful development of Covid vaccines in rapid time being the most recent example of cooperation to achieve a clear national goal. Building such partnerships in non crisis times around important goals could be an essential way of aligning technological advance with social and economic progress.

Different countries will, of course, have different priorities. And tech companies should be cognisant of both these national priorities and how emerging use cases of technology can help these goals be achieved. This goes back to political Motivations - the M of the MEDAL methodology that I socialised in IP33.

Understanding the motivations and goals of policymakers is a crucial first step to ensuring that tech is seen as relevant to national priorities. And directly contributing to those national (and international) goals and priorities will be important for tech companies to illustrate.

What are the skills required to meet societal goals?

I’ve made clear on a number of occasions how important skills are to maximising the power and impact. There is no point in aligning technological advance with societal goals if the society doesn’t have the skills to meet these goals.

This is likely to involve taking a much more strategic approach to the debate about tech and skills. Namely, asking the foundational question, “what does a society want to achieve using emerging technology and what are the skills required to do that?”

We know that technological advance is dramatically shrinking half life of a skill (the amount of time it takes for a skill to halve in value). And AI is likely to accelerate this impact even more. Such an acceleration means that societies have to consider the skills that they will need to achieve ambitious national goals with a much greater degree of clarity.

This means that the foundational skills and goals question cannot be asked as a one-time-only snapshot, but must be seen as an evolving process throughout someone’s working life. Effective collaboration between tech and other stakeholders is essential if societies are to have the ability to achieve the goals that come from an optimistic vision. And that is likely to mean tech companies, governments, business organisations, workers and others working together more effectively around the skills agenda.

How does regulation help to deliver a societal goal?

Both the Abundance and the Techno-Optimist agenda converge on the importance of ensuring that excessive regulation doesn’t get in the way of growth and societal goals. Of course, as I note above, they differ on what might constitute excessive regulation, just as they differ on societal goals. A difference in ends is likely to lead to a difference in means.

But that shouldn’t prevent both tech and governments thinking about regulation in a different way. Rather than starting with the process, isn’t it more important to start with the goals of a piece of regulation? This might make for more cohesive and understanding regulation and prevent the Christmas Tree effect of regulation taking on multiple, and sometimes contradictory, goals.

Crucially, it’s important to measure regulation against broader societal missions and goals, considering the question, “does this regulation make a societal priority more or less difficult to achieve?” This is a test that can be considered for both emerging regulations and existing regulations and might well be a test that will bring tech and governments closer together.